Adaptable by Nature — A Conversation with Mark Adams04.12.2019

In the core of the English town of Royal Leamington Spa, the Vitsœ building arises as a monolith in white. Its monochrome appearance isn’t out of place in this quietly developing community. Originally a spa town, Leamington has made room for manufacturing, with a burgeoning tech industry demographic and several commercial parks. But Vitsœ, surrounded by tall trees that hide residential surveys, stands alone. The massively simple space acts as the command post for design, operations and production, as well as housing a dance troupe. The Vitsœ ethos is inscribed in every facet of the building: the vast spaces are scantily decorated and transformable, suiting the needs of the user, returning to its original state with ease.

Mark Adams, Vitsœ’s managing director and most enduring employee (after Dieter Rams, that is) sits with Norse Projects, discussing the company’s fearless spirit in the pursuit of respecting and adapting to the natural world, working with Rams and the importance of ‘using’ as opposed to ‘consuming.’

Vitsœ corporate was in London for over twenty years. What spurred the movement to Leamington Spa?

We made the move to Leamington Spa because we had outgrown London. In our previous headquarters, which was in Camden, we were about 20% export. When we had left, we were about 65% export and had 40-foot containers coming into the centre of London every week. From a vehicle point of view, we couldn’t live in London anymore, but equally, from a financial point of view, we couldn’t live with London.

When Leamington was first suggested, I opened up one of those old route-planner maps and I put a piece of tracing paper over the southern half of England and Wales and just put crosses on where our key suppliers were. I saw that Leamington was pretty well bang centre of a two-hour radius so that most of our supply chain was within two hours. From that point of view, the location was good: it’s in the centre of the country, it’s good for distribution and there was a good railway connection back to London. Leamington’s a nice spa town that people would actually want to live in; recently voted as the best place to live in the UK. There were a lot of factors coming together, equally coupled with an old manufacturing heritage and digital gaming industry, that has been here for about five years, offering great tech resources. And finally, creatively as well, we’ve got a local dance group in here, so we were spanning the whole range of what Vitsœ does.

Your offices are rather breathtaking, with wide expanses, natural light and modular features. What is the importance behind building such a space?

Well it’s not an office and it’s not a factory — it’s a building. It’s a building because it’s got such a wide range of activities going on in it and we don’t want to pigeon-hole it into one particular area. We’re sitting here near our kitchen and we normally have a permanent exhibition space here. The contemporary dance group is just down there, we are building our furniture here, we have tech-team and product development just over there.

That range of functions coming into one building was critical — creating a building that we can adapt and change just like our furniture. Taking the thinking of our furniture up to a whole new scale. We’ve been in this building for two years and we’re now just going through a series of major changes in it. We could never have predicted what those changes would have been but we’re now able to adapt the building to suit our needs. The early signs are that the building is responding in the way that we hoped it could.

“Vitsœ is Vitsœ. Vitsœ is who we are, and we never think about artificially what we might place on it. We are only thinking about how we can express who we are and tell the world genuinely who we are.”

You have a longstanding history with Vitsœ; can you describe your relationship with the brand throughout your career?

You used the word brand and my relationship to that word is that it is absolutely banned at Vitsœ — so you’ve done well to even get it out of my lips. A brand is an artificial sign that is seared on the cows’ behind; it’s something that is applied from outside. Vitsœ is Vitsœ. Vitsœ is who we are, and we never think about artificially what we might place on it. We are only thinking about how we can express who we are and tell the world genuinely who we are.

My career with Vitsœ has spanned a long time. I was lucky, at the age of twenty-five, to discover Vitsœ and to be introduced to Niels Vitsœ, and then subsequently to Dieter Rams. I was coming into it as a child who was fascinated by the natural world. We had a fantastic biology department at school, I went on to study it at university; David Attenborough was an important influence on my life back then and amazingly he continues to be now into his 90s. But equally, I had been introduced to the world of good quality modern design. I had a very wide range of interests, and when I was introduced to Vitsœ, I actually found somewhere, where this wide range of influences could come together in one place; it took me a while to understand it.

Here we are in a building made of natural materials, naturally lit, naturally ventilated, views to the natural world behind me — modern design and an absolute appreciation of the natural world. I was very fortunate early in my life to find, and cultivate, all of those elements in one place; it’s probably why I’m fortunate in then having been able to develop that for my entire working career.

“Encouraging people to buy less furniture and make it last longer, repair it, put it in their wills and hand it on to the next generation: it’s a very tough business model. I happen to believe passionately that it’s the way that this world should work more.”

You saw a crumbling situation and turned it into an opportunity. What drove you to reach out to Vitsœ in the first place?

I’m not entirely sure of the question of why I reached out to Vitsœ. I discovered Vitsœ through a shop that I was visiting in the west end of London, funnily enough only about 200 meters away from where our current shop is now; I was buying one or two pieces from there for my first flat. I went in there, and they were installing a black shelving system on the wall. I asked what it was, and the owner of the shop says it was this guy called Dieter Rams, who’s actually Head of Design at Braun, but he’s also made some furniture. By that stage, I already had a Braun electric razor and a Braun alarm clock and made the connection to Dieter quickly. I was able to show enough interest, and a week later, the owner of that shop rang me up and said: would you be interested in working for us? He offered me a salary of about half of what I was then earning. I thought, if I don’t take the opportunity now to go into this world which I had not been educated to go into, I needed to find a way in; so I took the risk and stepped into it. That shop went bankrupt about four months after I joined it, but I’d spoken on the telephone twice to Niels Vitsoe. I jumped on an aeroplane, went to Frankfurt and introduced myself to a 73-year-old Niels Vitsoe as a 25-year-old man. That was where the relationship started. It was one of those sliding door moments.

Owing to your relationship with Vitsœ, you managed to keep the brand afloat. What do you attribute to repopulating Vitsœ’s success?

When I was talking with Dieter Rams earlier this year, I asked, “Do you realise it’s Vitsœ’s 60th anniversary now, and what’s your reaction to Vitsoe being 60 years old?” He said almost immediately, “It’s been tough. It was tough for Niels Vitsoe and it’s been tough for you.” That need to be tough comes from six decades of swimming against the tide, what Vitsœ does is not easy.

Encouraging people to buy less furniture and make it last longer, repair it, put it in their wills and hand it on to the next generation: it’s a very tough business model. I happen to believe passionately that it’s the way that this world should work more. We just cannot continue; the evidence is all around us that we cannot as we are. So, back to Dieter using that word ‘tough,’ that then relates back to me as the word tenacity. I have had to be tenacious above all else. There have probably been plenty of opportunities when I should have quit doing this and got a proper job, a much easier job because what we do at Vitsœ is absolutely not for the faint-hearted. Well, I think I’m not faint-hearted.

You had the opportunity to work with both Niels Vitsœ and Dieter Rams together. What was their dynamic like, after all these years of working together?

The first word that comes to mind about Niels Vitsœ and Dieter Rams together is mischievousness. Gary Hustwit’s Rams film premiered just over a year ago, and I was sitting there, in New York, for the premiere and halfway through the film, I realised I was in a theatre with lots of people laughing. I just got the loveliest feeling. I thought: Fantastic. Gary got across that Dieter has a really good sense of humour. You can see Dieters designs, go to his exhibitions, read any of the books; you get no clue of the character of Dieter Rams. Yes, a serious gentleman for sure, but with a lovely sense of humour; with Niels, that was there and that was probably something that connected us earlier on. A dry British sense of humour from here and they both had had an Anglophilic streak; Niels Vitsœ used to work with a British furniture maker in Denmark, his boss drove a Bentley and wore tweed — Niels was predisposed to the Brits.

Dieter has always been very grateful to the Brits. The first international award that he was given in 1961, when he was 29, was in London. A plastics award for the injection moulding that they were doing at Braun in those days. Dieter is a young German, relatively soon after the war, lots of bomb sites still in London, him speaking almost no English, came to London and the Brits presented him with this award and were very hospitable to him. I think those were the elements that allowed our triangle to come together, and let alone my biological background, my appreciation for the natural world and then rapidly understanding from both of them a tremendous sensitivity, seeing the way they used their fingers to touch and feel things, that we all have that sensitivity for the natural world.

In the battle of function versus fashion, how does Vitsœ win on both ends?

Vitsœ is absolutely not fashionable, not in any way shape or form. It would be the beginning of the end for us if we were to become fashionable. Everything we do at Vitsœ at all levels, it has to work very well and it also has to look good, in that order because that’s what good design is. Something that first and foremost, works well and secondly, looks good. It has often amused me, that for a business that is so resolutely unfashionable, unconcerned by fashion, we are very much appreciated by the fashion world. There is a real conundrum as to why so many people in the fashion world have our furniture in their homes, and yet they are locked into the cycle of twice a year having to titillate and titivate the world with yet another collection that, frankly, the world doesn’t need. Of course, the furniture world has fallen into that, having exhibitions every year where every company feels the need to present new products. We don’t take part in any trade exhibitions at all where new products would have to be presented because Vitsœ’s entire reason for being is to make things better, not to make things newer. And yet the fashion world has got somewhat trapped in a cycle of making things newer. In my humble opinion, there are too few fashion companies concentrating on making things better.

“We don’t know what the future holds for any of us. In fact, I think it’s quite frightening to think of the state of the climate emergency around us, and what the future will hold. But I remain absolutely confident that Vitsœ will be able to respond to that because Vitsœ knows who it is, what it is, what its purpose is — to bring a better quality of life to more people.”

With Vitsœ’s resolve to communicate order and honesty in its products, the object truly serves a purpose. How do you emphasise this to Vitsœ’s end user?

I’m often asked who Vitsœ’s customers are. Vitsœ’s customers are people who think beyond the end of their nose. They are normally intelligent human beings who are more aware of the world around them than maybe others are. There might be people that come into the world of Vitsœ, just thinking they’re buying a product at that stage. But gradually, as the journey unfolds, as the years go by, they realise that they’ve bought into something with many more layers of thoughtfulness and subtlety.

A word about Vitsœ: it’s a very subtle beast that can take a long time to get to know and understand. Like opera, or War and Peace, or the game of cricket, or any of these weird things that, on the surface, you may think, Oh what’s that all about. But once you get into it, then you discover more. Often, I think Vitsœ customers don’t really appreciate what’s going on until, say, they come to move to a new house five years in and then they realise what looked like that in this house can now look like something completely different in their new house. All of the thinking only starts to become apparent when you have to accommodate a change in your life. Let me give you a timely anecdote:

Two weeks ago, one of our customers said they bought a shelving system from us five years ago, had it in their home, put their home on the market and somebody came to look at their home and very much liked the shelves and asked if they could buy that with the house. The person selling the house declined and said they would be taking it to the new house because that’s what you do. The buyer said, “Please, will you leave it behind and tell us what price it would be.” The customer then gave them the price: at absolutely 100% full price. The person buying the house said that couldn’t be right as it’s second hand; the customer said, “Well no, I’m going to have to replace it in my new home it’s worth full price.” They sold that shelving system at full price with the home after having used it for five years.

I’ve been in this game for more than three decades, and stories like that still make me smile and pleasantly surprise me; we must be doing something right. I could sit here for the next two hours with you sharing similar anecdotes. That’s the way Vitsœ works.

How does the enterprise of service relate to you and your career?

Vitsœ is a service business that happens to make products. What Vitsœ will be in twenty or forty years’ time, I have no idea. But Vitsœ will still be a business that allows more people to live better with less, that lasts longer. That doesn’t mention shelves, or chairs, or furniture. The building we’re sitting in here can have five-hundred people performing an entirely digital function in it; there wouldn’t need to be anything physical going on.

We don’t know what the future holds for any of us. In fact, I think it’s quite frightening to think of the state of the climate emergency around us, and what the future will hold. But I remain absolutely confident that Vitsœ will be able to respond to that because Vitsœ knows who it is, what it is, what its purpose is — to bring a better quality of life to more people. That’s the challenge for us.

“The way in which we try to run Vitsœ is to be absolutely sympathetic to the natural world: trying to ally ourselves as closely as possible to the natural order and not fight against nature, but in the best possible terms, live with nature.”

As a zoology major, you must appreciate systems on micro and macro levels. Where do you fit between the two expanses?

With my biological background, my interest has been absolutely at the macro level: evolution and how it works. I have the greatest admiration for Charles Darwin, for unravelling how it all works, at the microlevel, the biochemical detail level. In University, I studied cellular processes, so genuinely, I can see the world through the full range. For me, I’m having to articulate the vision for Vitsœ and persuade everyone else to the merits of that vision, and to follow it. I think anybody here at Vitsœ will tell you that if there’s a risk, for me, it’s being distracted by the detail. The discipline I have to set for myself is not to be over-distracted by the minutia; I notice every detail. But really, your responsibility is to stay focused on that bigger and very long term picture.

There are projects that I am working on now for Vitsœ that easily span the next sixty years of the company. Not the next five, or ten years, in terms of the future of the company, but beyond all of us here, and how the company will endure. That will be the trick over certain years: why some companies manage to endure and why some very good companies do not manage to endure. That area is absolutely at the macro level, and where a lot of my time, thoughts and effort go.

What drew you to a systematised/systems-thinking approach to life?

As human beings, we are a part of nature. There has been a sense over the past fifty or one-hundred years that we are superior to it, that we are above it, and can dictate nature. I think, in recent years, we are learning absolutely that we are not superior to nature. Nature is biting back, and what we have to understand as human beings is that we are part of that wider order. The way in which we try to run Vitsœ is to be absolutely sympathetic to the natural world: trying to ally ourselves as closely as possible to the natural order and not fight against nature, but in the best possible terms, live with nature. The building we are sitting in hopefully shows that. Our challenge every day is to be closer to nature, not more distant from it.

How does efficiency, in terms of energy and adaptation, reflect your views? How does it reflect on Vitsoe’s ethos?

At Vitsœ, we are always striving for more efficiency. The word you used is efficiency, the word I would use is better: to make things better. Everywhere in our lives, in every decision, all of us take at whatever level on a daily basis, we can challenge ourselves to do less but do it better. Ask yourself ‘why do I need more of this?’ You don’t need more of that, have less of it, but see where you can do it better. My family’s policy on meat, for the last two decades, is that we eat relatively little meat in our home. But we eat good meat, we eat better meat. My policy on my clothes is having relatively few clothes, but clothes that will last, shoes that I can repair. All of my shoes, I’ve gotten more than twenty years out of them. One by one, it will cost you more, but rapidly, they will cost you less. That is applied in all areas of our lives: how can I do less but how can I do it better.

Explain the importance of sustainability, both commercially and personally.

The word sustainability rarely passes my lips. Just like the word design has become so devalued over the last two or three decades, the word sustainability is now rapidly becoming heavily devalued as well. But again, with my biological background, I am aware that we only have one planet, and there are more than seven billion of us on this planet. We all know the Three Planets Argument, where we are behaving in such a way that we are assuming, with the resources we are consuming, that we have three planets. We do not have three planets, and we rapidly, as a human race, have to get ourselves in a position where we are behaving absolutely compatible with the resources of the planet. Either we do that voluntarily or it is going to be involuntarily imposed upon us. The signs are all around us, in terms of the wildfires, the bleaching of the reefs, the intensity of storms, the droughts, the melting of the glaciers, the melting of the arctic, et cetera. The signs are all around us that we have to change and change very fast. The IPCC is warning us that we’ve only got 12 years and we are deeply in those 12 years already. We have to change hard and fast and it’s not happening quickly enough. I have the greatest admiration for the likes of Greta Thunberg, as a sixteen-year-old Swedish girl with Asperger’s syndrome, being the one who’s actually starting to wake us up, and we have to be woken up.

Obviously, Vitsoe stands as a beacon in this world of fast production. How do you underscore the brand’s adherence to its part in the circular economy?

I’ve worked for Vitsœ for more than half of Vitsoe’s sixty years of existence. There started to become a time around twenty years in when I started reading phrases like circular economy and sustainability, and all of the green words that came in around that. That’s what we’ve been doing at Vitsoe for forty years, and now for sixty years.

“We’ve got this ridiculous divergence in the way the human race is trying to behave. We have got to come back to nature’s path of allowing it to flatten off and be comfortable with who we are rather than this crazy situation we’re in of constantly desiring more. We can’t have more.”

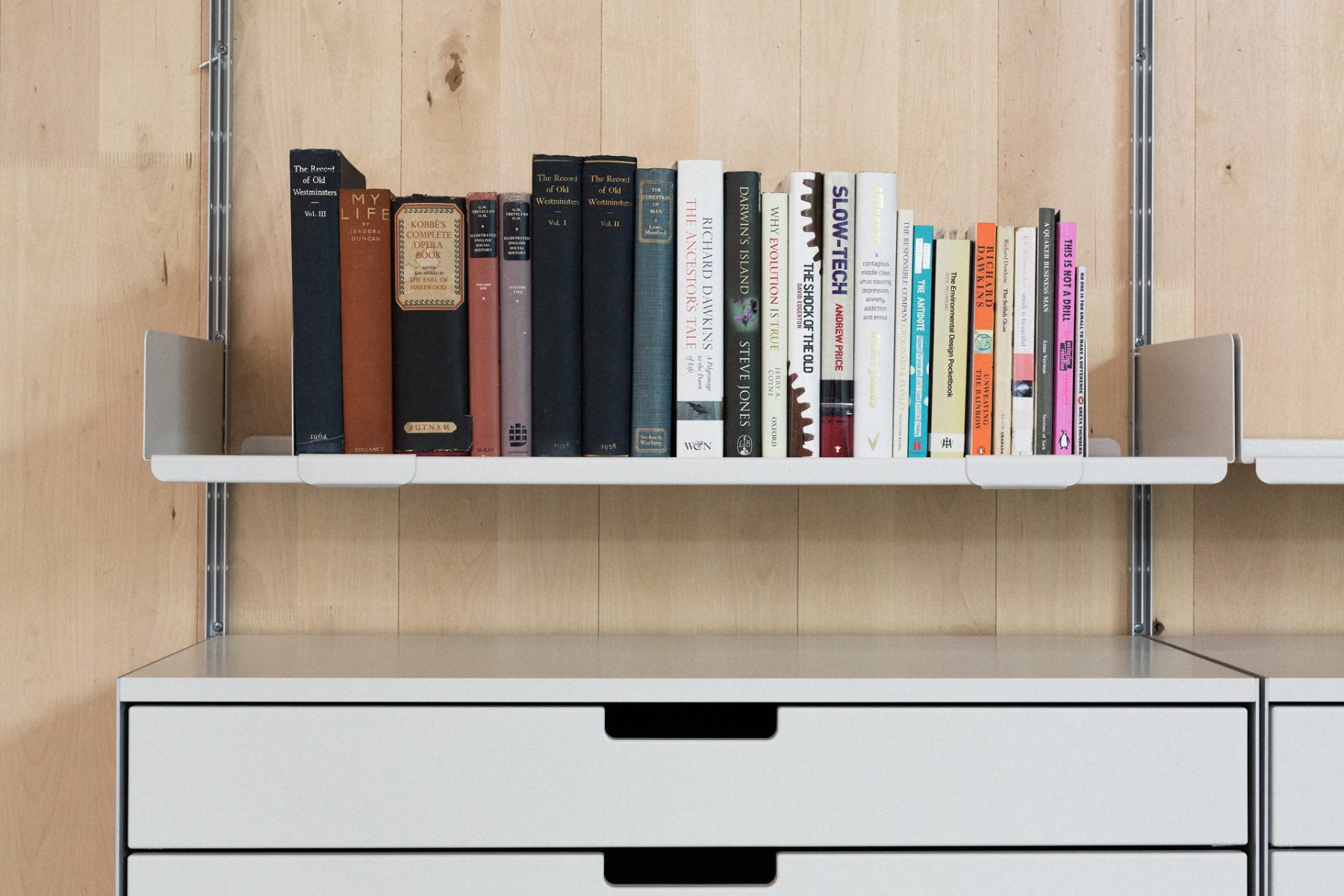

We have, as a business, behaved with absolute consistency for sixty years. The fact that I am sitting on a chair here from 1962 with a table from 1962 with a shelving system over there from 1960. The consistency of Vitsœ down through the decades is something that is truly remarkable and very unusual in other business.

The fact that we are the same business, the same products, the same designer Dieter Rams, at the age of 87, still with us. That has all been around a concentration on doing what we do here better and better: challenging ourselves every day in the way the natural world does. The process of evolution gradually finds its way to better solutions. Once it finds a good solution, that process can then become stable. The shark can be with us for hundreds of millions of years, or the crocodile or rhinoceros: because they are incredibly well-evolved solutions. Nature’s graph flattens off, while the human graph tries to go upwards and upwards. We’ve got this ridiculous divergence in the way the human race is trying to behave. We have got to come back to nature’s path of allowing it to flatten off and be comfortable with who we are rather than this crazy situation we’re in of constantly desiring more. We can’t have more.

How does Vitsœ offer an altruistic alternative, both for consumers and as a business model?

A book on the shelf over there was deeply influential on me as a teenager, Richard Dawkins first book, The Selfish Gene. It was the first time that I read the word altruism and then reading that book, you understand what it is and how it is the polar opposite of selfishness. I would argue that Vitsœ is as near as possible as it can become to running a business for altruistic reasons. That is, for the benefit of our customers, our suppliers, all of us, but equally for society at large. Or as Edmund Burke said, “for the unborn.” We are absolutely running Vitsœ for the unborn, and I’ve seen in my time in the company, the unborn coming in: the grandchildren inheriting what granny had bought forty or fifty years ago and then being identified by granny as the person to take on and respect this furniture.

Vitsœ is not run selfishly for the benefit or the enrichment of a few. We run Vitsœ absolutely in a way where anybody can share in it equally. We can all have a comfortable, respectable life, but nobody is benefitting at the expense of other people. When the industrial sustainability experts come in and look at us, as we’ve had many over the years, Cambridge University and Imperial College and more, they remark that we are highly unusual at Vitsœ at bearing our true costs. We do not try to outsource our costs to suppliers, our customers, society at large, or the unborn. Your cheap flight is going to be paid for by people that have not yet been born — we are quite the opposite. We are charging our customers the true and fair price for our furniture without trying to lay it off to other people. Our furniture costs what it costs because that’s what it costs for Vitsœ to exist in a way that is as fair as possible for our planet.

What is the emphasis behind ‘smarter’ consumerism?

The ‘consumer’ has within it that process of absorbing, using, then throwing away. Our customers are users; the challenge for us is to not only be users but be custodians and guardians of something. I think that’s what drives us every day at Vitsœ: how to bring more people into our world who previously behaved as consumers. We then might start to educate them on the benefits of being users.

“If there’s anything important in Niels Vitsœ’s last years, it was the sense of regret in him that he knew Vitsœ had been far ahead of its time, that he had never benefited from it having been ahead of its time. It is those individuals who are courageous enough to plant trees which they know they will never sit in the shade of. Those are the people I admire.”

How do you think consumerism is changing?

We have to stop being consumers, plain and simple. There is no more room for endless, limitless, inexorable consumption. We have to stop it.

What is your long-term vision for Vitsoe?

The same vision that is has always been: to allow more people to live better with less that lasts longer. It’s very simple, but the companies that do survive, in the long term, are those that have a clear sense of purpose, of why they are on the planet. That is quite the opposite of, “We’re here to make millions of pounds, dollars, euros, shareholders, executives and the like.” Those businesses do not survive in the long term; they exist for the purpose of making money.

Vitsœ is genuinely here, and this is probably why I have fought so hard to keep Vitsœ alive and develop it.

Vitsœ’s reason for being is very important for the changing world that we’re in. If there’s anything important in Niels Vitsœ’s last years, it was the sense of regret in him that he knew Vitsœ had been far ahead of its time, that he had never benefited from it having been ahead of its time. It is those individuals who are courageous enough to plant trees which they know they will never sit in the shade of. Those are the people I admire.

That was what Niels has done, and we hope to plant more trees going forward that we won’t see the benefit of. As human beings, we have to be thinking decades and centuries ahead, not just for the next quarter, or next year, or how we’re going to selfishly make more money in that time.