Greg Henry, a tundra ecologist from the University of British Columbia, has dedicated his life to researching the effects of climate change in Arctic ecosystems. For 44 years, he’s used an abandoned Royal Canadian Mounted Police outpost at Alexandra Fiord – or Alex, for short – on Ellesmere Island, in the Canadian High Arctic, as his research base. There, he established the longest-running tundra warming experiment in the world and has observed the shocking and rapid effects of climate change firsthand. But now, after over 40 summers and almost 10 cumulative years of incredible research and endless adventures under the midnight sun, he’s retired. And with no one to take over his research, he had to shut it all down this summer, 2023, after one final field season.

It’s the end of an era.

This is the story of Alex Fiord, of a rich and relatively unknown regional history, of game-changing ecological and climatic research, of a passionate and charismatic scientist and mentor, and of his final goodbye – not only to his life’s work but to a place he’s called home.

“I grew up in northern Ontario, Canada. As a kid, I read books by Farley Mowat – Never Cry Wolf, Lost in the Barrens, that kind of thing. They completely captured my imagination, and that fascination kind of ended up pointing me north. And so, I had always wanted to go to the Arctic. That’s all I really wanted to do.”

Getting to Alexandra Fiord is no easy feat. It’s remote and isolated, located at 79˚N on the central east coast of Ellesmere Island, in Nunavut; a High Arctic Canadian territory into which not one single road leads. The only access is by plane. This island, the 10th largest in the world and Canada’s northernmost, is home to less than 200 people, despite being roughly the same size as the UK. From Vancouver, it’s a 2-day, 4-flight trip: first to Ottawa, then onwards to Iqaluit. The last stop before the final push north to Alex is at Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island, where the Polar Continental Shelf Program – PCSP, an Arctic logistics and military base – is located.

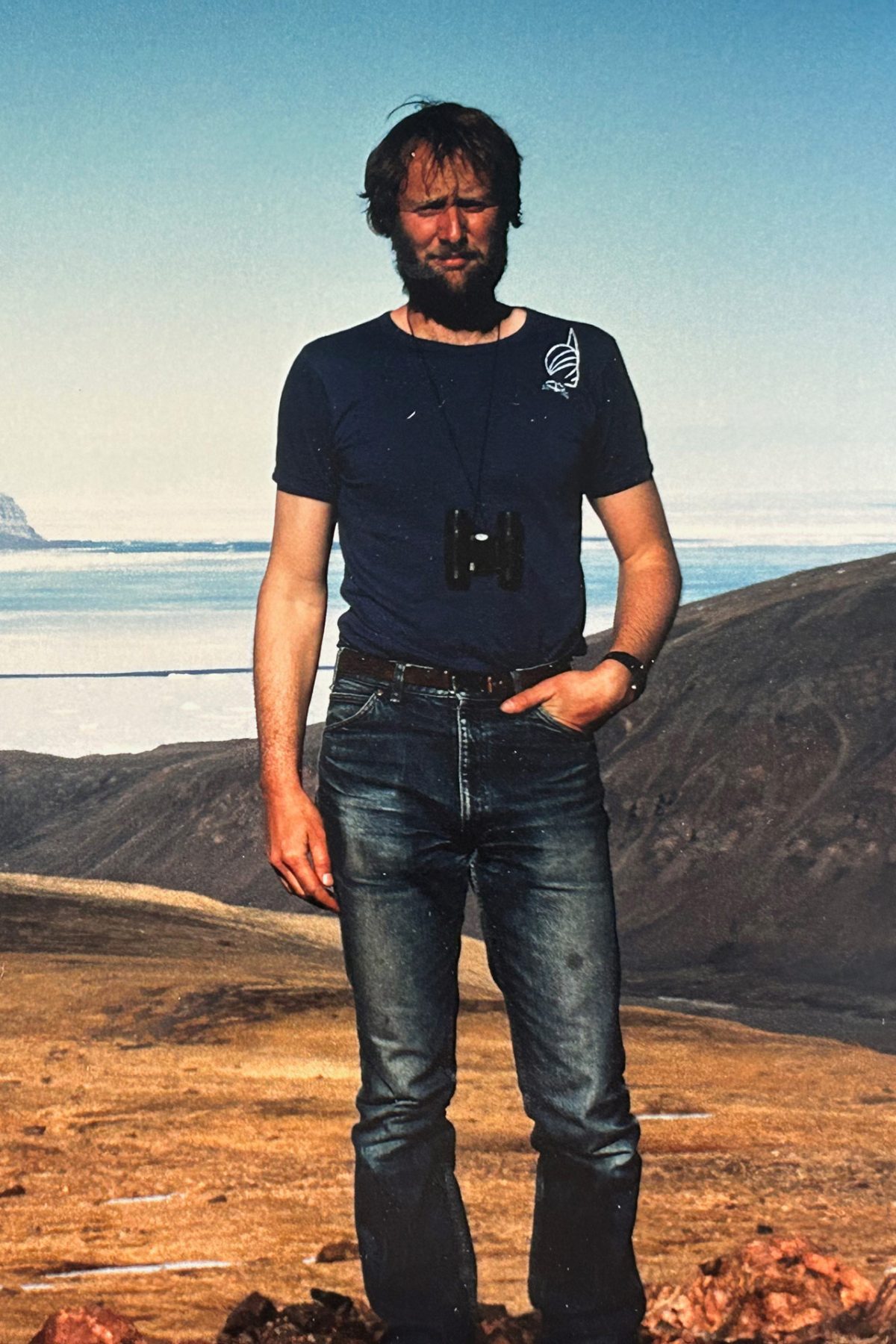

The first time Greg set foot at Alexandra Fiord, he was only 23 years old, fresh out of his MSc at Dalhousie and about to begin his PhD at the University of Toronto. This first trip in 1980 marked not only the start of decades of critical ecological and climate studies at Alexandra Fiord, but also Greg’s annual research trips and unwavering dedication to the site where he would carry out his life’s work.

“When we landed and I got out of the plane and looked around, I just went ‘WOW’. I was completely speechless and overwhelmed with excitement. And the sun didn’t go down – it was the first time I’d experienced that. I didn’t sleep for three days. I just ran around. I could not believe my luck, how beautiful it was, or the fact I was about to start this really interesting study on High Arctic wetlands for my PhD. I was over the moon, and I literally did not sleep for three days.”

Polar oases such as Alex are rare in the High Arctic, making up only about 6% of the Canadian High Arctic Archipelago. As an ‘ecological island’, a polar oasis in the otherwise largely barren and desert landscape, Alex presents a unique opportunity to study tundra ecosystem response to a warming global climate. Greg Henry’s true legacy in the field of Arctic science – not only at Alex Fiord, but far beyond – began in the early 1990s, with the establishment of the International Tundra Experiment (ITEX).

“Even in the 1980s, predictions from climate change models were showing that high latitude polar regions were going to have the earliest and most intense climate change relative to the rest of the planet. And because of that, the International Tundra Experiment was formed – a group of scientists who wanted to coordinate experiments across the polar regions so that we could understand what might happen to the tundra, and beyond, in the future.”

Greg set up the very first ITEX site at Alex in 1992 with a series of warming experiments and climate stations along a moisture gradient across the valley. These warming experiments, called open-top chambers (OTCs), were the first of their kind, and are essentially just small greenhouses – plexiglass structures with an open top. They warm up the tundra by 1-3°C, simulating the temperature increases predicted by climate change models. The ITEX network began as just one site at Alex but has since grown to include +20 sites in +10 countries in both Arctic, Antarctic, and alpine ecosystems. Now, there are thousands of OTCs scattered around the globe in all kinds of ecosystems.

“We’ve been involved in the annual report card that NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the United States, publishes. Our research has been cited in the IPCC (International Panel on Climate Change) reports, and agencies for the Arctic Council. So that’s very satisfying – that as a scientist, your measurement with a ruler actually ends up in an international climate change report.”

Over his 44 years at Alex, Greg has witnessed the significant effects of climate change firsthand: the glaciers surrounding the valley have retreated by hundreds of meters, average annual temperatures have increased by more than 2°C, the sea ice is melting much earlier, the frozen ground is thawing, weather patterns have changed drastically, the growing season is longer, and patterns of vegetation growth are unpredictable. The long-term warming experiments have revealed significant temperature increases, shifts in vegetation growth, and changes in plant communities. With warmer temperatures and longer growing seasons, plants are growing bigger, taller, and into higher elevations and latitudes. This ‘greening’ of the Arctic is one of the most important indicators of global climate change, and is changing the Arctic energy balance in ways that can further accelerate warming.

“One of the interesting things about coming up here for the last 44 years is that I’ve witnessed all these changes that you would expect to see maybe over thousands or tens of thousands or perhaps even hundreds of thousands of years – but I’ve witnessed them in just one lifetime. And that’s scary. I’ve been able to see all these things happen – like the glaciers melting and the weather patterns changing – but I wish I hadn’t.”

“It’s not just the scientific results that I’m very proud of. Perhaps the greatest pride I have, and some of the best results from the work at Alex, is the number of fantastic people that have come through here. And I’ve been very lucky, I guess, because I’ve attracted excellent students and have had the wonderful privilege of working with some of the brightest minds in polar ecology and Arctic ecology – minds that have been that have been wonderfully productive in the field and in publishing the results.”

But after over 44 summers and almost 10 cumulative years spent at Alexandra Fiord, Greg has retired. This summer, 2023, was his last at Alexandra Fiord, and it’s safe to say that wrapping everything up was both a significant emotional and logistical undertaking. Greg is hopeful that research continues at Alexandra Fiord, is some way, shape, or form. It likely will, but likely in a very different manner than has been going on for the past 44 years. While his long-term study has come to an end, there are still endless opportunities for interesting studies, as well as interest from a few researchers around the world. And they will have an incredible long-term dataset to lean on.

“There’s not a lot of places like Alexandra Fiord, and the value in that doesn’t escape me at all. And that’s one of the legacy pieces I hope comes out of me moving on – that all of the information from this site is available to anyone that needs it and who wants to work with the data in the future.”

“I do wish I’d had more time to contemplate the end of my time at Alexandra Fiord, including time to visit more of the special places around the valley and to walk along the trails, up the slopes and along the coast, enjoying the last days there. I also wish I had the time to sit and write about the end and how it felt. I’m just going to miss everything. It’s hard to put into words what this place does to me. But clearly it has done something, because I’ve managed to keep my life focused on coming back here for over 40 years. I’m going to miss the sound of my feet on the tundra. Walking on the tundra, walking on the sea ice, walking on the glaciers. I’m going to miss every single plant out there that I’ve come to know. I’m going to miss watching the birds, the seals, the bears. The science. The people, the laughs, and the sense of community every field season. The midnight sun and the ever-changing landscape. All of the adventures. I wish it didn’t have to end. But I’ve got it in me. In my spirit.”

Captured and documented by Jakob Gjerluff Ager and Sofie Agger

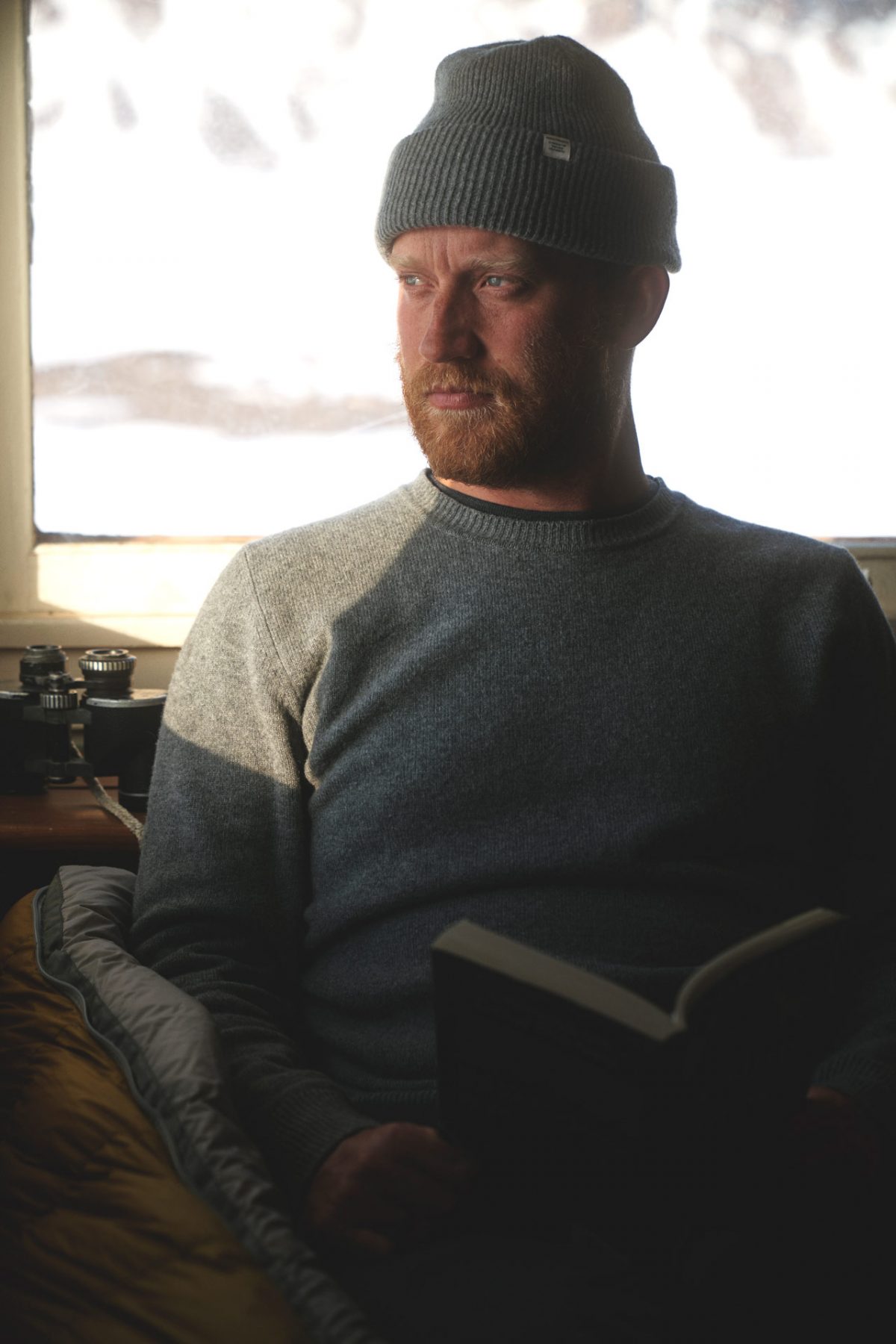

To enable the research team to conduct their study while shielded from the elements, Norse Projects provided Greg Henry and his colleagues with a versatile wardrobe system. This system offered comprehensive weather protection during fieldwork and ensured optimal comfort during downtime at basecamp.