A Conversation with Alastair Philip Wiper30.04.2020

Copenhagen-based photographer, Alastair Philip Wiper welcomed Norse Projects into his Østerbro home to discuss how his imagery probes the vast unknowns of human-made machinery and industry. By exhibiting the innards of modern society, the British photographer’s work taps into a universe that is often stifled by red tape and restricted access only seen by those on the ‘inside’

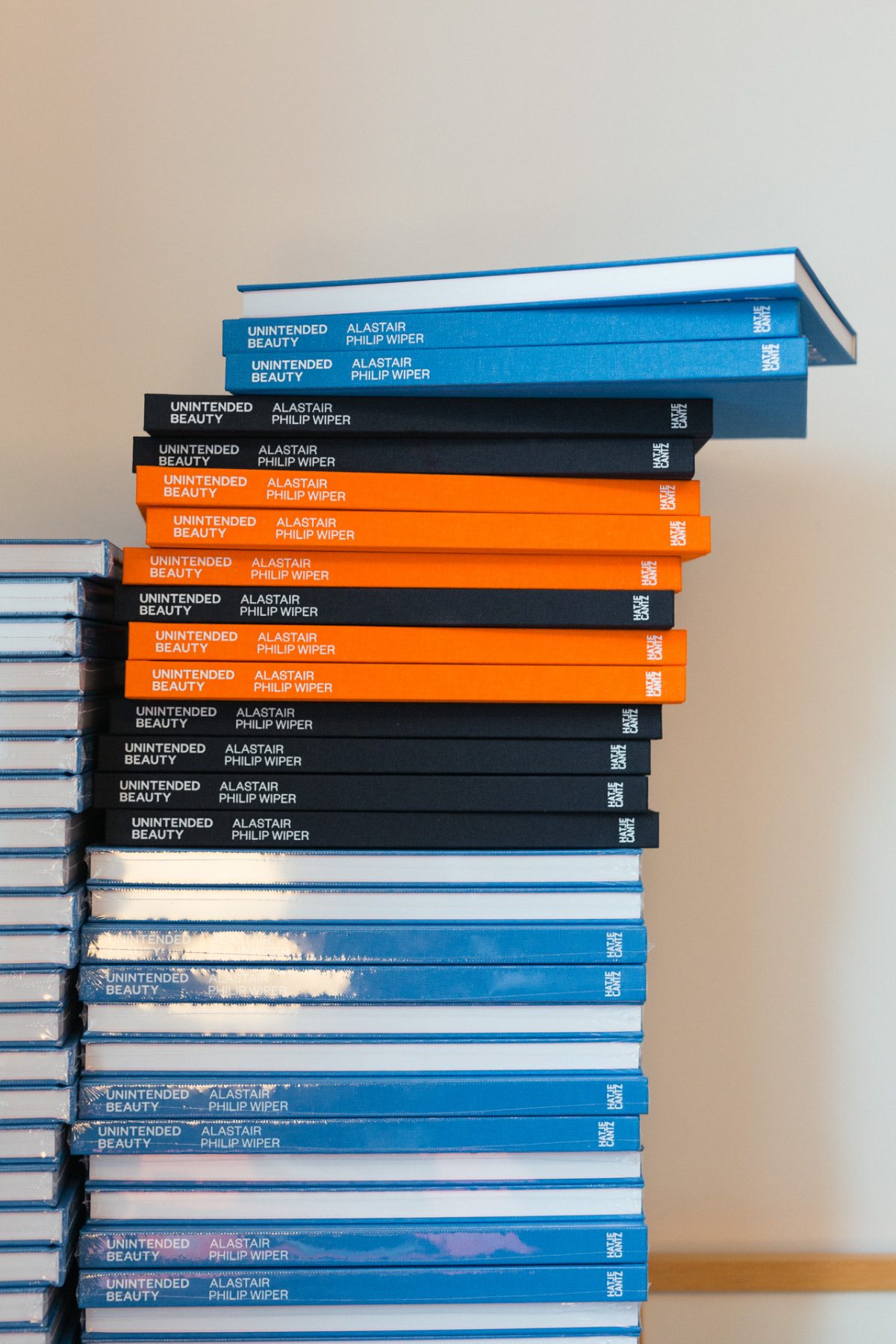

In his new book titled ‘Unintended Beauty’, Wiper draws back the curtain of an environment that most people rarely see; and as the title of his book implies, extends a curiosity that reveals the covert aesthetics of industry, research and production.

You’ve had a rather varied career history prior to being the photographer you are now. Would you mind sharing some of your exploits with us?

I grew up in Guildford, which is 25 miles southwest of London, and I went to university in Southampton when I was 17, 18 — studied philosophy and politics and finished when I was 21. Didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. I just wanted to get out of England and go travelling. I became a ski bum and did winter in France, then winter in Canada, summer in Greece, working at a crappy kitchen. And I was cooking all the time because I was interested in food and thought I could get a job cooking while I was travelling. Eventually, I ended up in Copenhagen because I met a girl.

At 24-years old, I knew that I didn’t want to be a chef forever, and wanted something else but didn’t know what. I decided to draw some T-shirts one day — I was kind of bored and had never done any art at school or anything like that and never done any photography. I just thought it would be fun. I eventually met a guy who could print them, so I did that and sold them, and I thought, “Okay, that’s what I’m going to do now. I’m going to make a clothing company. It was called Scribble. Looking back I’m a little embarrassed by it, but it’s always like this with hindsight. I then got a job working for Henrik Vibskov because I wanted to gain more experience doing this sort of thing, so I taught myself Illustrator and Photoshop and became their graphic guy. They also didn’t have a dedicated photographer, so I started doing all the lookbooks and runway shows. It was great and was my jumping off point to this profession.

So, naturally that leads to the next question of what drew you to working with visuals professionally?

One day I saw some pictures by a couple of old photographers that were working in the ’50s and ’60s. They were photographing oil refineries and factories and stuff like that. And it was like a light bulb moment for me. I was just like, “That’s what I want to do.” A whole world had opened up. I had never been interested in it, or I’d always thought it was a bit boring or corporate, and I just suddenly saw how like behind-the-scenes in all of these places that are all around us. There’s just like amazing stuff. And it would be easy because there’s shapes and colours and lines and content and material happening — it’s all just there, you know? To be there to be captured. And I would see amazing things while I was working and travel and it just ticked all the boxes. I went like 100% from that point, and that’s what I’m going to do, and I haven’t looked back.

Were there strong leanings or inclinations as a kid to go into this world?

When I was at a point at school where I could choose what subjects I wanted to go forward with, and art was one of them, no one said I should do it. And I wanted to, but someone said I should do this and this, instead. There’s extra energy coming to it later in life, and that’s been the fun part. Perhaps I missed out on some education in it, but now I’ve got this extra drive. With a lot of the stuff I do and the places I go, say with regards to science and technology, I wasn’t particularly into that when I was a kid. These are all new things for me now where I feel like I’m learning all the time. I still feel like a little kid in a lot of ways.

Tell us more about your ‘Lonely Fruit’ project.

That was the first exhibition I did — my first solo exhibition. And that was at Was Gallery in 2010 and when I started to get into photography. I started with a DSLR and then went and bought so many old film cameras and learned how to develop film and build a darkroom in my apartment. It was mostly kind of street photography and some portraits, but I guess the idea was to show people in slightly lonely situations. Not sad-lonely, but more like finding the humour in it, I like to think. It was kind of like isolating people in positions and trying to think about what was going on in their minds. I changed my style big time after that.

And that led you to industrial photography?

Like I just explained, seeing work from Wolfgang Sievers and Maurice Broomfield was like a lightbulb moment. These guys influenced me a lot. I just put all my beautiful old film cameras away in a cupboard and went full digital, full colour, as sharp as possible, as clean as possible and as vibrant as possible. So yeah, I also totally changed my style while at the same time, going for this approach and put all my beautiful film cameras away in a cupboard.

What did it take to build your portfolio? Especially, being without any experience in this new realm.

It took some lucky breaks and a lot of perseverance. I did some stuff at the beginning that was a bit silly like calling the Toyota customer care line and saying, “Hey, I’m a photographer. I want to photograph one of your factories. Who should I speak to?” And they say, “Nobody. Forget about it.” I had to learn early on, who is the person within Toyota that I need to speak to…and how do I approach them and tell them what I want to do? I got a lot of no’s, but I also got a couple of yes’s. That first couple of yes’s turned out to be the things that made my portfolio in the beginning. One, for instance, was at CERN in Switzerland, where they have the Large Hadron Collider.

I booked myself on a public tour, which you can do. At the same time, I wrote to the press office and said, “I’m a photographer, and can you show me anything that the public doesn’t get to see?” They wrote back and said, “Yeah, we’ve booked you on tour with an engineer, and he’s going to take you to these places.” When I met the engineer, he said, “Next time you want to come, don’t bother with the press office, just write to me, and I’ll show you around.” I went back two or three more times after that, and they hired me to come and take pictures. It all worked out really, really well. I had a couple of breaks like that where I found a person that just thought, “Yeah, this is fun. You can come and take pictures.” I feel like half of the art form is finding the right person and convincing them while at the same time, it’s still probably my least favourite part of what I do.

What was the project that helped you define your ‘style’?

I don’t think there was one. When I decided that this was what I wanted to do, I had like a clear vision of how the pictures should look and what I wanted to get out of going into these places. Most of it is just going on a gut feeling — I look for stuff, and I know what I’m looking for, and I try to get the thing it is that I have in mind.

Would you say that your subject matter is more engrossing than the act of capturing it?

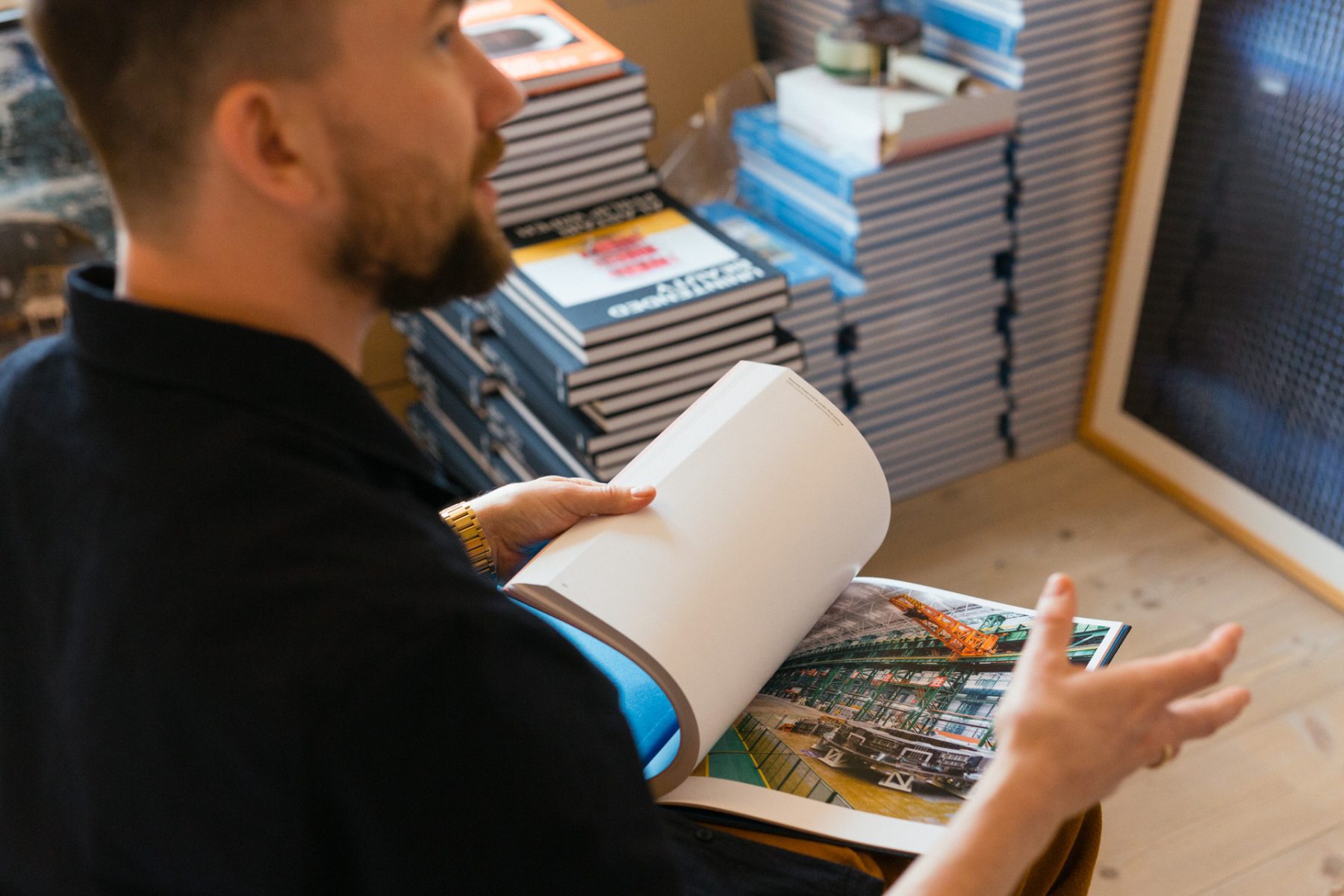

Yes. Definitely. When I was doing the Lonely Fruit exhibition, half the fun was the process of photography and developing film in the darkroom and everything that comes along with that. The gear and the lenses and everything was exciting, and now that’s become less and less the case. I see it much more now as a tool to get what I need. I think the places I get to visit are what makes my job the best in the world. I get to go to these amazing places around the world and see things that other people don’t get to see. Taking a picture is almost like an afterthought — it’s like an excuse to be there. The experience of being in the place, that’s the best feeling.

Outside of photography, is there a significance of industrialism to the human experience.

That’s a big question. I’ll take one part of it. I think there’s no doubt that the quality of life of pretty much everybody in the whole world has got infinitely better in the last one-hundred years — industry and technology has improved almost every aspect of our lives. Now, suddenly, we’re living in very confusing times because the things that I’m celebrating; namely human ingenuity, building machines and infrastructures. It’s becoming a symbol of what’s wrong with the world. For me, visiting these places hasn’t given me a more unobstructed view of what is right and what’s wrong — it has maybe made me more confused. There are so many sides and aspects of every story. You can’t just say, producing shoes in Indonesia in what looks to some people, a sweatshop, is terrible. Some communities rely on that factory, and if you close the factory down, you’re going to have a problem.

Visiting these places has convinced me that the world we live in is very complicated. One overwhelming thing that I’ve taken away is we don’t need to consume as much as we do. That seems like one thing I can kind of point out. There might be more ethical ways of how stuff gets produced and how it’s shipped and everything like that. But we don’t need as many pairs of shoes, for instance.

Your photography draws back the curtain and reveals a clandestine world. Is your intent to display different facets of our common perception?

I want to challenge what people think of as being beautiful. There are a lot of places the I’ve been to that are quite ugly places, but I think I’ve managed to find a pleasing angle in there. I’m not trying to pull the wool over anyone’s eyes. I’m just trying to show things from a different perspective, which I think is quite fun and trivial even — but my intent is not to tell anybody how to feel anything about these pictures. I think a lot of this machinery I photograph are becoming symbols of things like industrialisation and maybe a symbol of things we’re doing wrong for the environment. I might be more sensitive to it because of my position with regards to my work.

While I believe we as people need to change the way we do things, and the way we live our lives in terms of consumption, I also want to celebrate the ingenuity of the people that built these machines. It’s mind-boggling that humans can create these machines that solve our problems and provide for everything that we want and answer our questions about the beginning of life. Whatever happens with the environment, you can’t just stop using these machines as I think there’s an argument to be made that some of these machines are going to aid us in the end.

You’ve recently put out your second book. How does “Unintended Beauty” deviate from your work on “The Art of the Impossible”?

I was fortunate with The Art of the Impossible that I had a free rein from Bang & Olufsen to do whatever I wanted, which was amazing that they trusted me to do that. But I could go in to anywhere I wanted and photograph whatever I wanted. And go into the basement and find whatever I wanted. Ultimately I could decide how this book should be and which pictures should be in it. They trusted me to write the whole book as well, which I still think is quite amazing. It was always a book about Bang & Olufsen, whereas Unintended Beauty is really about my work and things that I want to show from around the world. I’m proud of the Bang & Olufsen book, but Unintended Beauty is broader and wide-ranging, and I think has more of my personality in it. I’ve chosen every single picture in there for a reason, an imagined idea in my head, not because they are telling a story say about Bang & Olufsen.

You mentioned you wrote the Bang & Olufsen book. How does writing factor into your process? There is a tone of voice there, and actually a bit of humour in it as well.

I started doing it because I started a blog. I realized that each place was like a little project in itself, and there were stories there. I wanted to have an outlet for that. At that time, when I first started, I wasn’t getting commissioned, and I couldn’t just call Wired, and say, “Hey, I’ve got a story. Are you up for it?” I saw each place I visited, it was like a little kind of story or project on its own, and it just seemed natural that there needed to be some text to go with it — something to keep the pictures from being too abstract. The images are still the most important thing, but the words give it context, and the viewer can decide how much they want to delve into the work.

Humour is essential to me when writing because I think people can imagine this subject matter being quite dry or sterile, and I want to give it life and make people smile. When I read back on my text where I’ve written something I thought was funny at the time, that’s the thing that makes me cringe the most.

What are your plans for future publications?

I have been doing a project about sex dolls and dildos and virtual reality porn and condom factories and producing the adult world that I’m hoping I’m going to make into a book at some point. There are human elements to it that I find interesting. I went to LA and started this project because I wanted to get some pictures of dildos in the book. I think these taboo subjects are significant for this project that it’s not just like straight shoe factories and laboratories. I wanted to capture aspects of life that people are more sensitive about. That’s why the slaughterhouse is really important for me, or a dildo factory. These things give the whole work more of completeness in my eyes.

What is a subject you have yet to photograph but have the urge to?

I get that question a lot. One thing I keep on thinking would be cool to see visually, or photograph is an atomic bomb going off. I don’t want to view it. I hope it never happens. But like, it looks like that kind of massive event and massive experience of this thing happening. But there are already a lot of good pictures of that, so I don’t know if I can add anything. I just think it would be a pretty amazing experience to photograph.

Is there something you’re invested in your personal photography that you’d like to explore on a commercial or editorial level?

No. Because I already do. One way I’m fortunate in that I work editorially, commercially, and personally, and they all mix. I can shoot a personal project that I can sell editorially, and I can shoot a commercial project and then use that in an exhibition. I don’t have to change the way I photograph for any of those three things. I feel really lucky about it because I think a lot of photographers have to change their commercial style.

I think that every company out there has stories to tell, just sitting behind the scenes. And I think they don’t realize it. I think it’s fun to go into these places and figure that out and show them that what’s going on here is cool.